New Concepts in Film Cooling for Turbine Blades

Aerospace

New Concepts in Film Cooling for Turbine Blades (LEW-TOPS-52)

Innovative, durable designs increase blade efficiency

Overview

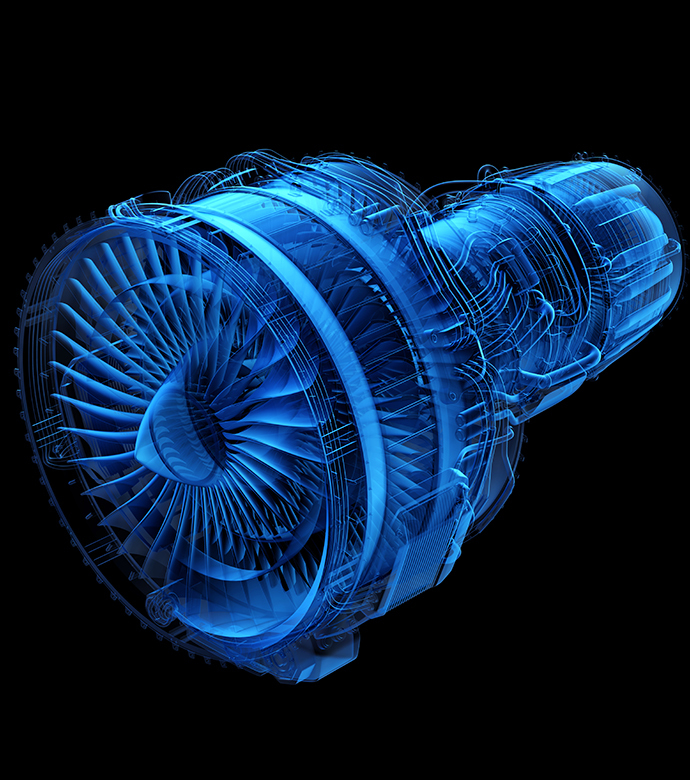

To run at maximum efficiency, turbine engines often experience temperatures of more than 2000 degrees Kelvin, and these elevated temperatures can lead to compromised integrity and failure of the blades. One method for addressing this problem is film cooling, in which cool air is bled from the compressor, ducted to one or more internal chambers of the turbine blades, and discharged through one or more cooling holes to form cooling jets. As a result of the cooling jets, convective heat transfer to the surface of the turbine blade can be reduced. Innovators at NASA's Glenn Research Center have developed two new ways to improve the effectiveness of film cooling. One involves using a shaped recess to create a counter-rotating vortex pair, splitting the incoming flow to a high-energy and a low-energy stream. The other innovation employs various techniques to mitigate the aerodynamic losses that sometime accompany film cooling. These novel approaches make film cooling a much more efficient and successful means of keeping turbine blades operable.

The Technology

In one of NASA Glenn's innovations, a shaped recess can be formed on a surface associated with fluid flow. Often V-shaped, this shaped recess can be configured to create or induce fluid effects, temperature effects, or shedding effects. For example, the shaped recess can be paired (upstream or downstream) with a cooling channel. The configuration of the shaped recess can mitigate the lift-off or separation of the cooling jets that are produced by the cooling channels, thus keeping the cooling jets trained on turbine blades and enhancing the effectiveness of the film-cooling process. The second innovation produced to improve film cooling addresses problems that occur when high-blowing ratios, such as those that occur during transient operation, threaten to diminish cooling effectiveness by creating jet detachment. To keep the cooling jet attached to the turbine blade, and also to spread the jet in the spanwise direction, NASA Glenn inventors have successfully used cooling holes that reduce loss by blowing in the upstream direction. In addition, fences may be used upstream of the holes to bend the cooling flow back toward the downstream direction to further reduce mixing losses. These two innovations represent a significant leap forward in making film cooling for turbine blades, and therefore the operation of turbine engines, more efficient.

Benefits

- Effective: Reduces aerodynamic losses while still permitting high-temperature operation

- Efficient: Lessens the chance of jet detachment and inefficient cooling

- Clean: Produces more efficient fuel combustion in turbine engines, and burns fuel in a more environmentally friendly way

- Easier to manufacture: Relies on a straightforward design that is simple to fabricate

Applications

- Gas turbines for ground power generation

- Combustion liners

- Jet engines

- High temperature / high pressure gas combustion cooling

Similar Results

Thermal Management for Aircraft Propulsion Systems

Aircraft thermal management systems typically comprise over half the mass associated with full electric power propulsion systems, with significant negative impact on fuel efficiency. In addition, the traditional method of using jet fuel to cool aircraft generators does not provide enough cooling for use in flight-weight cryogenic systems. Lastly, the much higher bus voltages required for flight-weight systems (4.5 kV vs. 270 V) introduce additional spark-ignition hazards associated with alternative cryogenic cooling fuels, including liquid methane or liquid hydrogen. The Glenn flight-weight thermal management system addresses all of these problems by using the considerable waste heat energy from turbogenerators to create a pressure wave thermoacoustically. This wave can then be delivered quietly and efficiently via routed ductwork to hollow pulse-tube coolers located near any component in the aircraft that requires cooling. The tubes can be fabricated in any length and can be curved to fit any space. This technology also allows waste heat energy to be used in at least four ways: 1) the waste heat energy can drive a thermoacoustics-based ambient or cryogenic heat pump; 2) it can be channeled directly into a thermoacoustic engine that generates power; 3) it can convectively preheat the fuel/ or air supplied to the aircraft engine; 4) it can drive a pulse-tube generator providing power. The delivered thermoacoustic power can provide cabin cooling as well as ambient/cryogenic cooling of converter, cables, and motors. In addition, this power can be converted to local electric power through the use of a transducer (such as a linear alternator) or piezoelectrics. Further, the efficient thermal management system enables the size, mass, and resultant cost of the radiating fins to be reduced. Glenn's system offers an efficient method of cooling next-generation flight-weight electric aircraft with significant benefits for fuel efficiency and safety.

Additively Manufactured Oscillating Heat Pipe for High Performance Cooling in High Temperature Applications

The advent of additive manufacturing makes available new and innovative integrated thermal management systems, including integrating an oscillating Heat Pipe (OHP) into the leading edge of a hypersonic vehicle for rapid dissipation of large quantities of heat. OHPs have interconnected capillary channels filled with a working fluid that forms a train of liquid plugs and vapor bubbles to facilitate rapid heat transfer. Multiple additive manufacturing techniques may be used, including powder bed fusion, binder jetting, metal material extrusion, directed energy deposit, sheet lamination, ultrasonic, and electrochemical techniques. These high performance OHPs can be made with materials such as Refractory High Entropy Alloys (RHEAs) that can withstand high temperature applications. The structure of the OHP can be integrated into the constructed leading edge. The benefits include a heat transport capacity of 10 to 100 times greater than before. Integrated OHPs avoid the bends or welds in traditional heat pipes, especially at the locations where the highest thermal stresses might cause thermal-structural failure of a leading edge. Alternating the diameters of the OHP channels alleviate start-up issues typically found in liquid metal oscillating heat pipe designs in high temperature applications by aiding in the instigation of a circulating flow due to multiple forces acting upon the working fluid.

3D-Printed Injector for Cryogenic Fluid Management

NASA's TVS Augmented Injector includes an internal heat exchanger, a fluid injector spray head, and an external surface condensation heat exchanger - all combined with multiple intertwined flow paths containing liquid, two-phase, and gaseous working fluid. The TVS provides a source of coolant to the injector, which chills the incoming fluid flow. This cooled flow promotes condensation of the tank ullage dropping pressure and maintains incoming fluid flow. The system eliminates the potential for a stalled fill condition and reduces tank pressure during cryogenic fluid transfer. During fill operations, the tank vent can be closed early in the process before fluid is introduced, and, in some cases, the tank vent may not even need to be opened. Furthermore, the TVS Augmented Injector can remove sufficient thermal energy to reach a 100% liquid level in the receiver tank. A cryo-cooler can be used in place the TVS flow circuit for a zero-loss system. The TVS Augmented Injector couples internal fluid flow cooling and external surface ullage gas condensation into a single, compact package that can be mounted to small tank flanges for minimal impact insertion into any vessel. The injector is printed as one part using additive manufacturing, resulting in part count reduction, improved reproducibility, shorter lead times, and reduced cost compared to conventional approaches.

The injector may be of particular interest in applications where cryogenic fluid is expensive, fluid loss through vents is problematic, and/or achieving high filling levels would be helpful. The injector can benefit typical cryogenic fluid transfer between containers or, alternatively, can serve as a tank pressure control device for long-term storage using a fluid recirculation system that pumps fluid through the injector and sprays cooled liquid back into the tank. Additionally, where ISRU processes are employed, the injector can be used to liquefy incoming propellant streams.

Stirling Thermoacoustic Power Converter and Magnetostrictive Alternator

Glenn's thermoacoustic power converter reshapes the conventional Stirling engine from a toroidal shape into a straight colinear arrangement. Instead of relying on failure-prone mechanical inertance and compliance tubes, this design achieves acoustical resonance by using electronic components. In a typical Stirling engine, the acoustical wave travels around a toroid and reflects back, forming a standing wave. In Glenn's device, by contrast, the wave instead travels in a straight plane where a transducer receives the acoustical wave and electrical components modulate the signal. A second transducer on the diametrically opposed side reintroduces the acoustic wave with the correct phasing to achieve amplification and resonance. Glenn's design allows the transducers to operate at high frequency while presenting a mass rather than stiffness impedance.

Glenn's magnetostrictive alternator uses stacked magnetostrictive materials under a biased magnetic and stress-induced compression. The acoustic energy from the engine travels through an impedance-matching layer (which can be formed from aerogel materials) that is physically connected to the magnetostrictive mass. Compression bolts keep the structure under compressive strain, allowing for the micron-scale compression of the magnetostrictive material and eliminating the need for bearings. The alternating compression and expansion of the magnetostrictive material creates an alternating magnetic field that then induces an electric current in a coil wound around the stack. This alternator produces electrical power from the acoustic pressure wave and, when the resonant frequency is tuned to match the engine, can replace the linear alternator to great effect.

Thin Film Sensor for Ultra High-Temp Measurement

The thin film sensor’s principal advantage lies in its potential to take high frequency temperature measurements from the surface of a reentering spacecraft while simultaneously withstanding the high temperature and oxidizing environment encountered. This data provides engineers with operational phase measurements used to refine the spacecraft’s operational envelope and track flight hardware behavior in addition to providing high frequency temperature measurements that can inform the physics of a boundary layer.

Mismatches in coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE) are expected in TPS-based sensor applications because the metallic materials used for temperature sensing have thermal expansion rates that differ from the rates of the substrate and coating materials in the TPS. At high temperatures during reentry, this mismatch in CTE can create a significant strain differential between the metallic sensor, sensor leads, and the materials to which the sensor and leads are bonded.

High frequency response temperature measurements on the surface of entry spacecraft are not currently possible above ~700 F with existing measurement capabilities. This shortcoming is primarily due to the need for robust sensor behavior at temperatures of several thousand degrees F. The sensor design of this technology preserves the integrity of sensor components while enhancing its high temperature functionality.

The thin film temperature sensor has a technology readiness level (TRL) 5 (Component and/or breadboard validation in relevant environment) and is now available for patent licensing. Please note that NASA does not manufacture products itself for commercial sale.