Pilot Assisted Check Valve for Low Pressure Applications

mechanical and fluid systems

Pilot Assisted Check Valve for Low Pressure Applications (MFS-TOPS-79)

Maintains sealing load at low pressure differentials, resulting in lower leakage rates

Overview

Inventors at NASA have developed an advanced check valve with a pressure sensing design that allows the valve to crack open at low pressure differentials while still providing the required sealing stress on the valve seat at all pressures below cracking pressure. The design of the valve also allows it to maintain sealing stress on the seat regardless of downstream pressure. In low pressure conditions of 100 psi or less, sealing issues often occur when a low cracking pressure is desired. Alternative check valves are unable to provide the required sealing stress on the valve seat. This results in seat damage and eventual leak issues due to the rotation of internal parts relative to the seat. This valve provides a solution to low pressure applications with stringent leak requirements.

The Technology

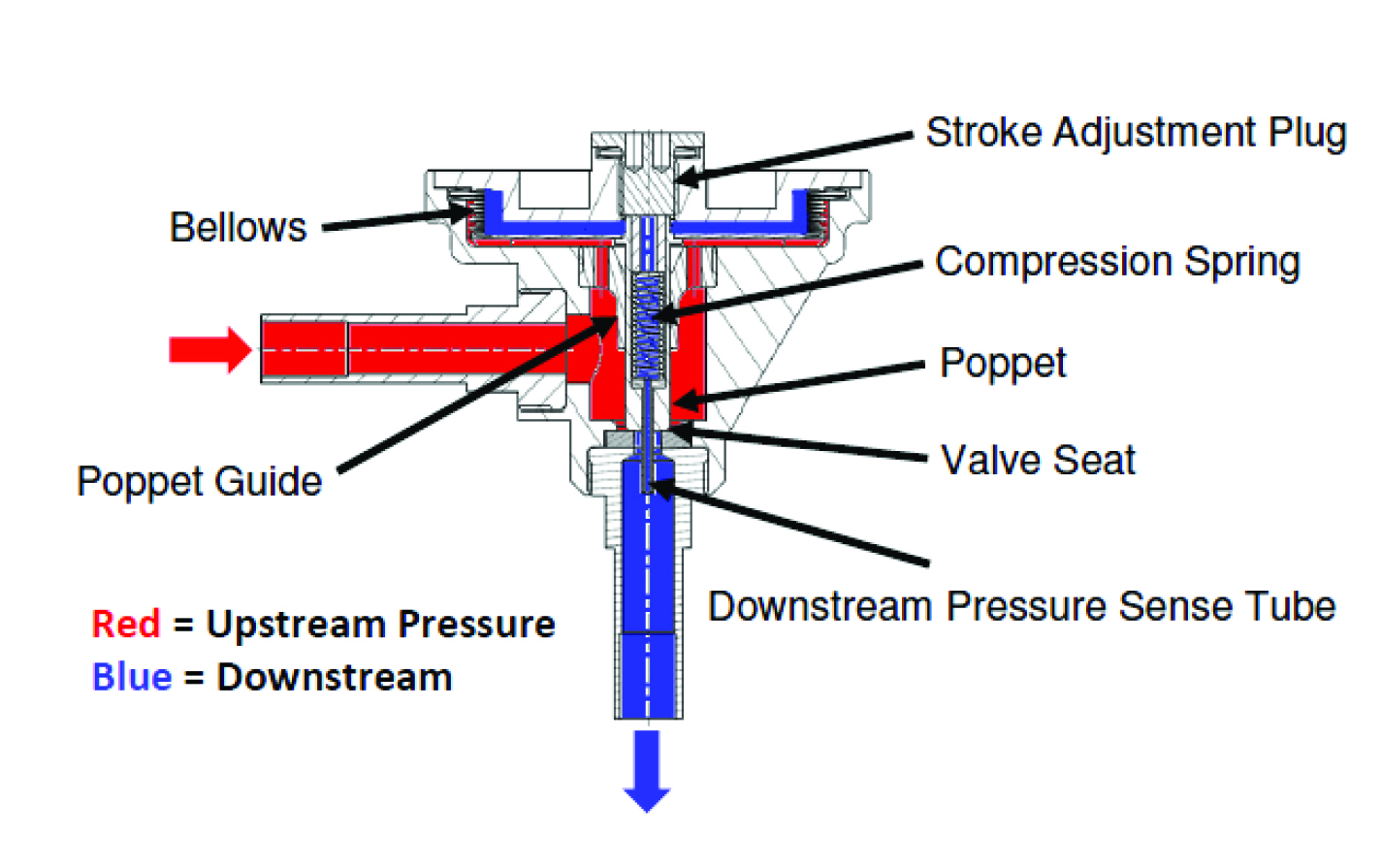

Check valves are traditionally designed as a simple poppet/spring system where the spring is designed to equal the force created from the sealing area of the valve seat multiplied by the cracking pressure. Since the valve seat diameter in these types of valves are relatively small, less than 0.5 inches diameter, a low cracking pressure required for back pressure relief devices results in a low spring preload. When sealing in the reverse direction, the typical 20 psid storage pressure of the cryogenic fluid is not enough pressure force to provide adequate sealing stress. To better control the cracking pressure and sealing force, a bellows mechanism was added to a poppet check valve (see Figure 2). The bellows serves as a reference pressure gauge; once the targeted pressure differential is reached, the bellows compresses and snaps the valve open. Prior to reaching the desired crack pressure differential, the bellows diaphragm is fully expanded, providing sufficient seal forces to prevent valve flow (including reverse flow) and undesired internal leakage. Room temperature testing of cracking pressure, full flow pressure, and flow capacity all showed improvements. The overall results of the test proved to be 10-20 times greater than conventional check valves with no internal leakage at three different pressure differentials.

Benefits

- Improved internal leakage

- Prevents seat damage

- Has a low cracking pressure

- Maintains sealing stress on the seat regardless of downstream pressure

Applications

- Cryogenic propulsion applications

- Cryogenic manufacturing

- Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) storage and transport

- Nuclear Safety Systems

- Vacuum Jacketed Systems

- Any low-pressure environment that has strict requirements against chemistry mixing or venting

Similar Results

Low-Cost, Long-Lasting Valve Seal

NASA's technique simplifies the seat installation process by requiring less installation equipment, eliminating the need for unnecessary apparatus such as fasteners and retainers. Multiple seals can be installed simultaneously, saving both time and money.

NASA has tested the long-term performance of a solenoid actuated valve with a seat that was fitted using the new installation technique. The valve was fabricated and tested to determine high-cycle and internal leakage performance for an inductive pulsed plasma thruster (IPPT) application for in-space propulsion. The valve demonstrated the capability to throttle the gas flow rate while maintaining low leakage rates of less than

10-3 standard cubic centimeters per second (sccss) of helium (He) at the beginning of the valves lifetime. The IPPT solenoid actuated valve test successfully reached 1 million cycles with desirable leakage performance, which is beyond traditional solenoid valve applications requirements. Future design iterations can further enhance the valve's life span and performance.

The seat seal installation method is most applicable to small valve instruments that have a small orifice of 0.5 inches or less.

Magnetically Damped Check Valve

NASA's Magnetically Damped Check Valve invention is a damping technology for eliminating chatter in passive valves. Because valve failure in space missions can cause catastrophic failure, NASA sought to create a more reliable check valve damper. The new damper includes the attachment of a magnet to the poppet in a check valve to provide stabilizing forces that optimize flow and pressure conditions. Test results have proven that the Magnetically Damped Check Valve offers substantial benefits.

The Magnetically Damped Check Valve works over a wide range of flow dynamics and eliminated chatter under all flow conditions tested, allowing valves to operate under various flow rates and pressures without a risk of degradation or total destruction from chatter. This technology could provide a more simple and cost-effective solution for valve manufacturers and system designers than solutions currently available in the market.

Applications for the new valve include use in aerospace or industrial processes. NASA's damping technology was originally designed for check valves, but could also benefit pressure regulators, relief valves, shuttle valves, bellows sealed valves or other passive valves.

Self-aligning Poppet

Without improvements in valve technologies, propellant and commodity losses will likely make long-duration space missions (e.g., to Mars) infeasible. Cryogenic valve leakage is often a result of misalignment and the seat seal not being perpendicular relative to the poppet. Conventional valve designs attempt to control alignment through tight tolerances across several mechanical interfaces, bolted or welded joints, machined part surfaces, etc. However, because such tight tolerances are difficult to maintain, leakage remains an issue.

Traditional poppets are not self-aligning, and thus require large forces to “crush” the poppet and seat together in order to overcome misalignment and create a tight seal. In contrast, NASA’s poppet valve self-aligns the poppet to the valve seat to minimize leakage. Once the poppet and seat are precisely self-aligned, careful seat crush is provided. Owing to this unique design, the invention substantially reduces the energy required to make a tight seal – reducing size, weight, and power requirements relative to traditional valves. Testing at MSFC showed that NASA’s poppet reduces leakage rates of traditional aerospace cryogenic valves (~1000 SCIM) by three orders of magnitude, resulting in leakage rates suitable for long-duration space missions (~1 SCIM).

NASA’s self-aligning poppet was originally targeted for aerospace cryogenic valve systems, especially for long-duration manned space missions – making the invention an attractive solution for aerospace valve vendors. The invention may also find use in the petrochemical or other industries that require sealing to prevent critical or hazardous chemicals from leaking into the environment. Generally, the invention may be suitable for any application requiring low-leak and/or long duration storage of expensive or limited resource commodities (e.g., cryogenic gases, natural gas, nuclear engines, etc).

Floating Piston Valve

Instead of looking to improve current valve designs, a new type of valve was conceived that not only addresses recurring failures but could operate at very high pressures and flow rates, while maintaining high reliability and longevity. The valve design is applicable for pressures ranging from 15-15,000+ psi, and incorporates a floating piston design, used for controlling a flow of a pressurized working fluid.

The balanced, floating piston valve design has a wide range of potential applications in all sizes and pressure ranges. The extremely simple design and few parts makes the design inherently reliable, simple to manufacture, and easy to maintain. The valve concept works with soft or hard metal seats, and the closing force is easily adjustable so that any closing force desired can be created. The fact that no adjustment is required in the design, ensures valve performance throughout valve life and operation.

This valve has many unique features and design advantages over conventional valve concepts:

- The largest advantage is the elimination of the valve stem and any conventional actuator, reduces physical size and cost.

- It is constructed with only 5 parts.

- It eliminates the need for many seals, which reduces failure, downtime and maintenance while increasing reliability and seat life.

- The flow path is always axially and radially symmetric, eliminating almost all of the flow induced thrust loads - even during transition from closed to open.

Cryogenic Cam Butterfly Valve

A globe valve controls flow by translating a disc over an opening. A butterfly valve controls flow by rotating a disc in an opening. The disc and seat of a butterfly valve have to create a tight seal exactly when the disc meets the 90 degree mark. If additional torque (energy) is added to the actuator of a butterfly valve, the disc will rotate past 90 degrees and the valve will open again. Therefore, with a standard butterfly valve, additional actuator energy cannot be added to reduce or minimize seat leakage, like with a globe valve.

The novel Cryogenic Cam Butterfly Valve (CCBV) design functions like a typical butterfly valve, rotated to open or close the valve. However, unlike a typical butterfly valve disc that can only rotate, the CCBV can be translated and rotated to control flow. The main parts of the CCBV include a body, disc, cam shaft, torsion spring and 180 degree actuator. In the full open position, disc rotation is 0 degrees and the disc is approximately perpendicular to the valve body to enable maximum flow. However, unlike a typical butterfly valve where the disc is not pinned to the shaft, the CCBV has a preloaded torsion spring mounted concentrically on the shaft with the spring legs against the disc, and a pin to keep the disc coupled to the shaft. The torsion spring is preloaded with sufficient torque so that the disc/shaft assembly acts like the disc is rigidly pinned to the shaft. The first 90 degrees of the actuator and shaft rotation rotates the disc, just like a typical butterfly valve; however, at approximately 90 degrees, one edge of the disc makes contact with the body seat, while the opposite edge is slightly off of the body seat. At this point, the disc can no longer rotate. The cam shaft then converts rotatory motion into translational motion. Because of the cam shaft lobes, as the actuator continues to rotate the shaft, the disc can now translate towards the body, and enables more of the disc to seal against the body seat. Therefore, all actuator and shaft rotation beyond 90 degrees translates the disc towards the body seat to create a tighter seal, similar to how globe valve functions. When the valve is in this position, seat leakage will be reduced and with additional actuator rotation, stopped. Eventually, a tight seal is formed in the full closed position. Then, with opposite shaft rotation, the valve will open. The CCBV incorporated the advantages of a globe to achieve tight seals from ambient to cryogenic temperatures.